UK inflation fell more sharply than economists expected in November, offering the first meaningful relief to households in months and reshaping the outlook for interest rates just days before the Bank of England meets.

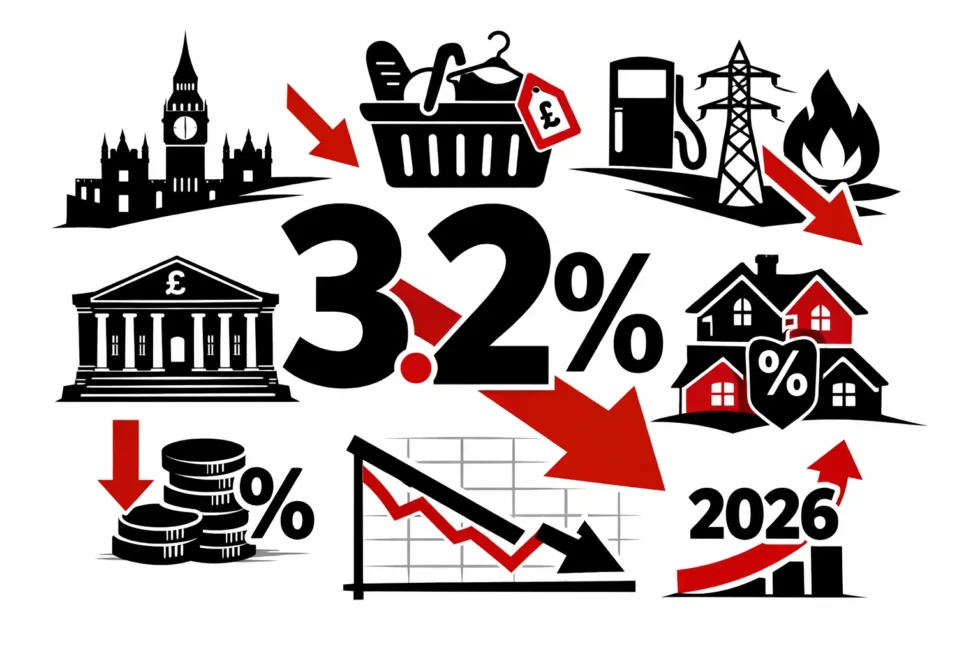

The Office for National Statistics said consumer prices rose by 3.2 per cent year-on-year, down from 3.6 per cent in October — the lowest reading since March and well below the market forecast of 3.5 per cent. The slowdown comes at a fragile moment for the economy. GDP has slipped into contraction, unemployment is edging higher and consumer confidence remains weak — conditions that typically force central banks to loosen monetary policy.

Although inflation is still above the Bank’s 2 per cent target, the pace of the decline now indicates that price pressures are fading faster than policymakers had assumed. As The WP Times reports, citing official ONS figures and leading British business media.

What pushed inflation lower

Three forces combined to drive the November fall: falling food prices, aggressive retail discounting and easing energy costs. The biggest impact came from groceries. ONS data shows that food and non-alcoholic drink prices fell by 0.2 per cent in a single month — a rare occurrence in November, when supermarkets normally raise prices ahead of Christmas.

The sharpest declines were recorded in bread, cereals, dairy products, sugar, jam and chocolate — staple items that dominate most household shopping baskets. On an annual basis, food inflation slowed from 4.9 per cent to 4.2 per cent, easing pressure after two years of steep increases.

Grant Fitzner, chief economist at the ONS, said the breadth of the fall was unusually wide:

“Lower food prices, which traditionally rise at this time of year, were the main driver, particularly for cakes, biscuits and breakfast cereals. Tobacco and women’s clothing also pulled inflation lower.”

Black Friday turned into an inflation event

Retailers amplified the effect. This year’s Black Friday promotions were deeper and more widespread than in 2024, pushing clothing and footwear prices down by 0.3 per cent between October and November. The steepest cuts came in women’s fashion, including trousers, skirts and winter clothing, as chains competed for increasingly cautious consumers.

The British Retail Consortium said intense price competition forced many retailers to sacrifice margins in order to protect volumes. Kris Hamer, its director of insight, said:

“With shoppers beginning their Christmas spending, retailers used much bigger promotions than last year, which helped pull prices down across both clothing and food.”

Energy is no longer driving inflation

Energy — the main engine of Britain’s inflation shock — is now acting as a stabiliser rather than a threat.According to Hargreaves Lansdown, electricity prices are rising by just 2.8 per cent year-on-year and gas by 2.1 per cent, a fraction of the levels seen during the energy crisis. In addition, government reforms taking effect from April are expected to cut the average household bill by around £150 a year, further dampening inflation in 2026. Sarah Coles, head of personal finance at Hargreaves Lansdown, said:

“Energy prices are no longer pushing inflation higher, which gives households and the wider economy much-needed breathing space.”

Why the Bank of England is now under pressure to cut rates

The inflation data lands just before the Monetary Policy Committee meets, and it fundamentally alters the policy debate. With inflation falling faster than forecast, GDP shrinking and unemployment rising, markets now see a rate cut as highly likely — potentially the fourth reduction of 2025. Lower borrowing costs would ease mortgage repayments, business loans and consumer credit, providing support to the economy as it heads into 2026.

What this means for households

For families, November’s inflation drop matters less as a headline and more in how it changes the next three to six months— on supermarket shelves, in monthly repayments and in wage negotiations.

1) Day-to-day costs are cooling, but relief will be uneven

The immediate benefit is psychological as much as financial: households are no longer seeing weekly “price creep” across the basics at the same intensity as earlier in 2025. Food inflation slowing — and a rare month-on-month dip — suggests supermarkets are being forced to compete harder, with promotions returning to staples rather than just treats.

But the effect will land differently by household type:

- Families with children feel it most through the “basket” items: cereals, bread, dairy, snacks and lunchbox basics. Even a small deceleration here matters because it hits multiple times a week.

- Single households benefit less from grocery easing if they’re exposed to rent rises, council tax, commuting and utilities — categories that do not fall quickly.

- People on tight budgets will see the gap between “headline inflation” and lived reality: the products you actually buy may remain expensive, even if the overall index cools.

2) Borrowing costs could start moving first, not last

The bigger practical shift is the interest-rate narrative. If the Bank of England moves towards cuts, the first households to feel it are not necessarily the ones who most need help — it depends on the kind of debt you carry:

- Variable-rate mortgages / trackers: these tend to respond quickly. A cut can reduce monthly payments almost immediately, though the size depends on the loan and the lender’s pass-through.

- Fixed-rate mortgages: many households are locked in. Relief comes when you refinance — meaning the benefit arrives at the end of a fix, not the day rates fall. The key question becomes: when is your renewal date?

- Renters: landlords’ borrowing costs can influence rents, but with a lag and rarely one-for-one. In practice, rent levels are driven more by supply, local demand and tenancy churn than by a single rate decision.

- Consumer debt (credit cards, personal loans, overdrafts): rates may ease slowly. Lenders often move down more cautiously than they moved up, and many products remain priced at a premium.

The most useful household action is timing. If your mortgage fix ends in 2026, you’re effectively watching two markets: inflation (which drives the Bank’s confidence) and swap rates (which feed into fixed mortgage pricing). In plain terms: inflation falling improves the chances that your next deal is less painful than the last.

3) Savings: a quiet trade-off is coming

Rate cuts can help borrowers but begin to squeeze savers. Many families have been using higher savings rates as a small counterweight to higher bills. If policy loosens, expect:

- Instant-access savings rates to start drifting down first

- Fixed-term savings to become more attractive for those who want to lock in today’s returns before they fall

That creates a new divide: households with cash buffers may want to protect interest income; households with debt want the opposite.

4) Government measures help, but they don’t erase pressure

Rachel Reeves is right to frame easing inflation as relief, and measures such as a rail-fare freeze and lower energy charges can reduce specific pain points. But the public mood is shaped less by “inflation falling” and more by a blunt reality: prices rose sharply for two years, and they did not come back down — they merely rose more slowly.

Why life still feels expensive

Inflation falling does not mean prices fall; it means they rise less quickly. That distinction explains why households often feel the headline is disconnected from the weekly shop.

Three structural forces keep prices “sticky”:

1) Costs inside the supply chain remain high

Even with easing energy, producers still face:

- higher wage bills (tight labour markets and pay settlements)

- transport and logistics costs that haven’t reset to pre-crisis norms

- raw materials that fluctuate but remain elevated in key categories

Retailers can reduce prices only where competition is fierce and margins allow it. Where margins are thin — or inputs are fixed — prices stay high.

2) Households notice essentials, not averages

The CPI is a basket. Families judge affordability through what they buy most often: groceries, rent, commuting, childcare, utilities. If the categories that hit you weekly remain expensive, it overrides any relief from a cheaper TV or discounted clothing line.

3) “Catch-up” pricing is still working through the system

A lot of businesses delayed price rises during the worst of the squeeze and then adjusted later. That delayed pass-through makes the cost-of-living crisis feel longer than the inflation chart suggests. Karen Betts’s point captures the reality: families are still dealing with a higher baseline, even if the upward pressure is easing.

A structural turning point

November’s reading looks like more than noise because it shows multiple engines of inflation cooling at once — food, retail pricing dynamics and energy. When only one category improves, inflation can bounce back. When several cool together, it starts to look like a trend. What makes this potentially significant:

1) Inflation is becoming less “shock-driven”

Britain’s inflation surge was powered by extraordinary shocks: energy, supply chains, global commodity spikes. Cooling across essentials suggests the economy is moving back towards a more normal pattern — where inflation is shaped by wages, demand and competition rather than crisis pricing.

2) Policy can pivot from firefighting to managing the slowdown

For the Bank of England, this is the shift from “how do we crush inflation?” to “how do we avoid damaging growth while inflation returns to target?” That is why rate cuts are now being discussed as a near-term possibility rather than a distant one.

3) Households get a clearer horizon — not instant relief

For families, the real implication is not that life becomes cheap again. It’s that the trajectory becomes less frightening: bills stop climbing so fast, wage increases stretch further, and borrowing costs stop tightening.

The test for 2026 will be whether this cooling persists without a new shock. If food and energy keep easing and wage growth doesn’t re-ignite price pressures, the cost-of-living squeeze shifts from acute crisis to slower recovery — still hard, but finally measurable.

Read about the life of Westminster and Pimlico district, London and the world. 24/7 news with fresh and useful updates on culture, business, technology and city life: Why is the Bank of England poised to cut UK interest rates before Christmas — and who wins